The tabletop roleplaying game has finally made it to PC. I’m not talking about an RPG that borrows a few ideas from Dungeons & Dragons, either. This is a proper translation of pen-and-paper mechanics – dice, a game master, cooperative roleplaying – into a videogame setting. Unsurprisingly, this combination of the old and new comes courtesy of Larian Studios, as part of Divinity: Original Sin II. Its new Game Master mode provides one of the most exciting and creative multiplayer experiences I’ve ever had. If you’ve ever wanted to play true D&D online, you’ll likely find this a mode perfectly catered to your tastes.

Incredible adventures await you in the best RPGs on PC.

Game Master mode is two things: an incredibly powerful tool kit, and an asymmetrical multiplayer game. As the former, it provides a player the means to create a campaign, built up from maps and encounters. These campaigns can then be shared with the community via Steam Workshop, or played with a group of friends. When playing Game Master mode, one person (possibly the creator of the campaign) plays as the game master, who controls all monsters, NPCs, and even the environment, while other players command their own traditional RPG protagonist.

Where Divinity: Original Sin II differs from other games based around the ‘one player is the enemy’ games is how it grants ultimate power to the players and game master. While you can stick to the game’s pre-programmed combat systems, players can roleplay and suggest other, more out-the-box solutions, which are resolved through dice rolls. Mechanics can be created on the fly. Dialogue options are replaced by genuine conversation. The limits of a computer game are removed almost wholesale.

The system is incredibly adaptable, so much so that you can basically play any RPG you like within it. Thanks to the inclusion of digital dice, if there’s a rule that Divinity doesn’t support, you can replicate it in-game by following the rulebook of another RPG. To prove this, at a recent hands-on event Larian experimented with their own tool kit and replicated the first starter quest in Dungeons & Dragons 5th Edition. Our game master would follow the D&D campaign, and we would be able to use spells and rolls from the classic tabletop game if we wanted to. I was soon to learn just how adaptable the system was.

A party of three adventurers begin their long trek along the Sword Coast, travelling from Neverwinter to Phandelver. They’re escorting a caravan filled with vital goods (cheeses and hams). Their employer, a hardy dwarf fellow, has ridden out ahead of them and will meet the trio in Phandelver.

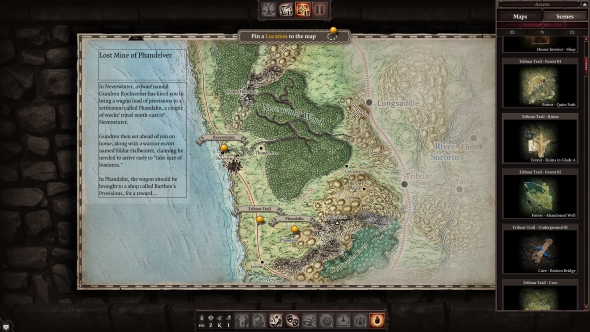

As a game master, you begin a campaign by creating a world map. Divinity will ship with its own map art, but you can import any image you fancy into the template. Doing a Lord of the Rings-themed campaign? Just grab a map of Middle-earth from Google images. The map can then be ‘pinned’ with areas. For our D&D inspired quest, pins for Neverwinter, Phandelver, a forest area, and some fortress ruins were attached to the map. When travelling to new places, an Indiana Jones-like red line snakes from pin-to-pin.

The heroes Matt, Simon, and Dave walk for many miles, but encounter a worrying sight as they follow the forest path. Blocking their way is a huge, ferocious wolf, standing atop the corpse of a ravaged horse.

When hero players arrive at a pin, they’re transported to a ‘scene’. These scenes are level maps where the roleplaying happens. Larian hope to include more than 100 pre-made scenes with Divinity, covering fantasy staples like castles, forests, and mountain paths. More advanced users can use Divinity’s developer toolkit to create something more elaborate (say, a Death Star if you really wanted to go to town and make a Star Wars campaign), but the vast collection of pre-made scenes and items will ensure the mode is accessible to everyone.

The first scene our GM has created for this quest is a forest containing a few collectable items and our first enemy. To achieve this, the GM has decorated the pre-made map with herbs, treasure chests, a dead horse, and a wolf. It’s a process very similar to creating a house in The Sims; just choose the right items form a catalogue panel and click to add them to the world. Part of the fun is adding items to the right location. For example, the GM has planted a herb among a set of pre-existing flora on the map. It’s not obvious, and may be missed by players unwilling to scour the environment. But that’s the joy of being a GM; which of your created opportunities will players take?

The trio approach the wolf hesitantly. They need to get past it, but there’s no immediately obvious route. What should they do? Perhaps they could throw a branch into the trees, and the wolf may follow it? Or should they draw their weapons and strike the beast down here and now?

In a normal game of Divinity, coming across an enemy like a wolf typically means one thing: battle. This doesn’t gel with the more free-form imagination of a tabletop game, and so the Game Master mode offers players a more adaptive approach to these kind of situations. Vignettes are GM-created cards displayed to hero players that can contain art, prose, and a selection of multiple choice answers. In our current example, the card details the wolf and the dead horse, and offers three options: back away, create a diversion, or fight. It’s up to the hero players to make that decision, and the GM must react to their choice.

Simon pulls a broken branch from the undergrowth, weighing it in his palm to find the best throwing grip. With an over-arm swing he hurls it far into the trees behind the wolf. The loud snap of branches as it collides with overhanging tree canopy causes the wolf to sprint away from the horse and into the depths of the forest.

With the wolf out the way, the heroes notice that the horse has an arrow protruding from its neck. The wolf did not kill this stallion, an archer did.

There is no system in Divinity to deal with thrown sticks, and that’s where the Game Master mode’s dice roller comes in. The game master can provide any or all players with a dice to roll (all the classics, from D4 up to D100), and this is the primary way to resolve actions not supported by Divinity’s programmed systems. In this example, the GM decides that in order to successfully throw a stick to distract the wolf, a player must roll 12 or more on a D20. Among ourselves we decide who will throw, and the GM sends a dice roll prompt to that player. Luckily the roll succeeds, and the wolf runs away.

You can see how these dice rolls allow far more experimentation. With the actual intelligence of a game master, you don’t have to rely on specific parameters of a pre-programmed game engine. Upon investigating the dead horse, one of us decides to try and work out who fired the arrow by analysing the projectile. On the fly, our GM decides to use the D&D rules on intelligence. We roll a D20 and use our character’s intelligence stats as a bonus modifier. It’s not enough to pass the test, but together we realise that our employer who rode ahead of us was likely ambushed.

The trio of heroes trek past the wolf’s den and find themselves in the ruins of an old fortress. The road curves ahead, but the way is blocked by a huge collection of chests, crates, and barrels. A second dead horse lies bleeding on the dirt track. Among the arches of the ruins, wide, shiny eyes peer out. The scuttle of leather-bound feet and long fingernails leaves no question as to who occupies this collapsed fort: goblins.

In this new scene, a couple of goblins are wandering around the ruins, while a third with a bow is perched on a high tower. The GM is physically controlling them; there’s no scripting here. This means he can make them react accordingly to what we do, increasing the immersion of the story.

Talking of immersion, the GM has access to the atmosphere panel, which allows them to subtly alter the world with lighting and sound. For example, they can add in the sound of circling seagulls, or cause night to instantly (or even slowly) fall.

Thankfully for our party, while the goblins are incredibly stupid, they’re not hostile. Among ourselves we decide to attempt to trick them into letting us past. And so begins a completely unscripted conversation between the heroes and the GM, who adopts his best goblin impression. We explain to the greenskins that we’re transporting corpses infected with the plague, and if we hang around too long there’s a good chance they could catch it. Our party leader is a cleric, and his religious uniform seems to aid in convincing the goblins. Of course, when I say ‘convince the goblins’, I mean that the GM decreed our excuse satisfactory. The green monstrosities let us past their blockade, and even help us move the boxes.

Naturally, this situation could have gone any number of ways. A second group of journalists playing in a different room tried to intimidate their way past the blockade by demonstrating that their warrior wore a belt made of goblin heads. Rather than scare them off, the goblins put up a fight and locked them in a dungeon. This involved a little bit of downtime while the GM quickly assembled a new scene to imprison them in. And that’s the beauty of Game Master mode; you can easily change the game to suit the journey you want to embark upon.

Upon reaching Phandelver, the heroes’ contact appears worried. His friend failed to make it to the town, despite heading out before them. Things slowly become clear; the dead horses were those of the trio’s employer, the arrows in their neck fired by a goblin ranger. With the promise of an extra 50 gold, the adventurers head back to the ruins with a plan.

The joy of pen-and-paper combat is that it doesn’t have to be quite as rigid as videogame battle. Were we attacking these goblins in Divinity’s campaign, our only real option would be to initiate turn-based combat and make the most of the game’s substantial elemental mixes. Thanks to the GM, though, in Game Master mode we can try something slightly more elaborate.

Our plan is to gather the goblins close for a conversation and then use one of my battle mage’s spells to blind them. We’d then use the nearby barrels to douse them in oil, set them alight, and be on our merry way.

Would that it were so simple.

Despite having let us through previously, the goblins have forgotten us and our tale of plagued corpses. One of them insists on checking the wagon. After a quick whisper we agree, and instruct Simon to ‘take him to the wagon’. As our warrior and the suspicious goblin disappear behind our completely empty cart, I cast the blinding light spell. Since this happens outside of Divinity’s combat engine, the GM simply sets a blind status effect on the two nearby goblins, and through direct control makes them stumble about. I take the lead to knock over the oil barrels, rolling a D20 to check strength. I fail, suddenly putting the entire plan in jeopardy. To make matters worse, Simon’s backstab on the curious goblin fails to kill it. Panicking, we simply set fire to the oil barrel as it stands, causing a massive explosion that sets fire to literally everything on screen. Both the goblins and our heroes slowly roast.

Perhaps we should have just engaged in normal Divinity combat. That may have gone a little smoother. That’s the beauty of Game Master mode, though; you can use all of Divinity’s normal systems if you wish, but the inclusion of the game master’s tools means you can try something even stranger than Divinity’s already-weird mechanics. And while it sounds incredibly complicated, it really isn’t. An entire campaign can be put together by simply clicking and dropping items, and even a barebones creation can provide a brilliant session thanks to the magic of roleplaying. After disappointments like Sword Coast Legends’ Dungeon Master mode, it feels doubly impressive that Larian have made a game that really does live up to the idea of your imagination being the only limits.